스테인 글라스의 비밀 Stained Glass: The Splendid History of an Ancient Art Form That Still Dazzles Today

Stained Glass: The Splendid History of an Ancient Art Form That Still Dazzles Today

By Kelly Richman-Abdou on April 28, 2019

Sainte-Chapelle in Paris (Photo: Stock Photos from SIAATH/Shutterstock) This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

스테인 글라스의 비밀 수천년 동안, 장인들은 반짝이는 유리에서 영감을 찾았다. 어떤 형태로든 유리는 정교한 예술 작품을 만들어 낼 수 있다. 그러나, 색이 입혀지면 변화무쌍해진다. 창과 예배 장소와 자주 연관되어 있지만, 스테인 글라스는 고대 컵에서부터 현대 설치물에 이르기까지 모든 종류의 예술에 채택되고 각색되어 왔다. 그러나 우리가 오래된 스테인 글라스의 역사를 추적하기 전에, 이 특성을 이해하는 것은 중요하다. 스테인 글래스란 무엇인가? "스테인 글라스"는 제조 공정 중에 금속 산화물로 색칠된 유리를 말한다. 다른 첨가제는 다른 색조를 생성하여 장인들이 전략적으로 특정 색상의 유리를 생산하도록 한다. 예를 들어, 녹은 유리에 구리 산화물을 첨가하면 녹색과 푸른 색조로 최고의 화려함을 보인다. 일단 유리가 식으면, 장식 예술 작품을 만들 수 있다. 황기철 콘페이퍼 에디터 큐레이터 Ki Cheol Hwang, conpaper editor, curator |

edited by kcontents

For thousands of years, artisans have found inspiration in glistening glass. In any form, glass can produce exquisite works of art. However, when colored, the medium climbs to kaleidoscopic new heights.

Though often associated with windows and places of worship, stained glass has been adopted and adapted for all kinds of art, from ancient cups to contemporary installations. Before we trace the age-old history of stained glass, however, it’s important to understand the medium’s key characteristics.

What is Stained Glass?

“Stained glass” refers to glass that has been colored by metallic oxides during the manufacturing process. Different additives produce different hues, allowing artisans to strategically produce glass of specific colors. For example, adding copper oxides to molten glass will culminate in green and blue tones.

Photo: Stock Photos from HelloRF Zcool/Shutterstock

Once the glass has cooled, it can be pieced together to produce works of decorative art. These fragments can be held in place by various materials, including lead, stone, and copper foil.

History

Evidence of stained glass dates back to the Ancient Roman Empire, when craftsman began using colored glass to produce decorative wares. While few fully in-tact stained glass pieces from this period exist, the Lycurgus Cup indicates that this practice emerged as early as the 4th century.

The Lycurgus Cup, 4th century CE (Photo: The British Museum CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The Lycurgus Cup is an ornamental drinking glass made out of dichroic glass—a medium that changes color depending on the direction of the light. When lit from the inside, the cup produces a red glow; when illuminated from the outside, it has an opaque green appearance.

How did early Roman artisans craft such a cup? Today, the process used to create this piece is shrouded in mystery. Though historians are certain gold and silver droplets in the glass are responsible for its color-changing qualities, they believe that it may have been produced by accident, as no other work of dichroic glass from this time features such a drastic color contrast.

The Lycurgus Cup, 4th century CE (Photo: The British Museum CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

“The Lycurgus Cup demonstrates a short-lived technology developed in the fourth century CE by Roman glass-workers,” a team of art historians explain in The Lycurgus Cup – A Roman Nanotechnology. “We now understand that these effects are due to the development of nanoparticles in the glass. However, the inability to control the colourant process meant that relatively few glasses of this type were produced, and even fewer survive.”

Still, the Lycurgus Cup is celebrated as one of the most important ancient glassworks, with art historian Donald Harden going so far as to call it “the most spectacular glass of the period, fittingly decorated, which we know to have existed.”

MEDIEVAL MONASTERIES

By the 7th century, glassmakers began shifting their attention from wares to windows. As expected, these stained glass windows were used to adorn abbeys, convents, and other religious buildings, with St. Paul’s Monastery in Jarrow, England as the earliest known example.

Created when the monastic building was founded in 686 CE, fragments of these centuries-old windows were excavated by archaeologist Rosemary Cramp in 1973. While the original composition of the blue, green, gold, and yellow pieces is unknown, the monastery compiled them into collages in order to offer viewers an idea of how beautiful these windows would have been.

“When we picked it up, it was like picking up jewels,” Professor Rosemary Cramp explains in an audio guide for the site, “and it still gives an idea of how precious it must have been.”

GOTHIC CATHEDRALS

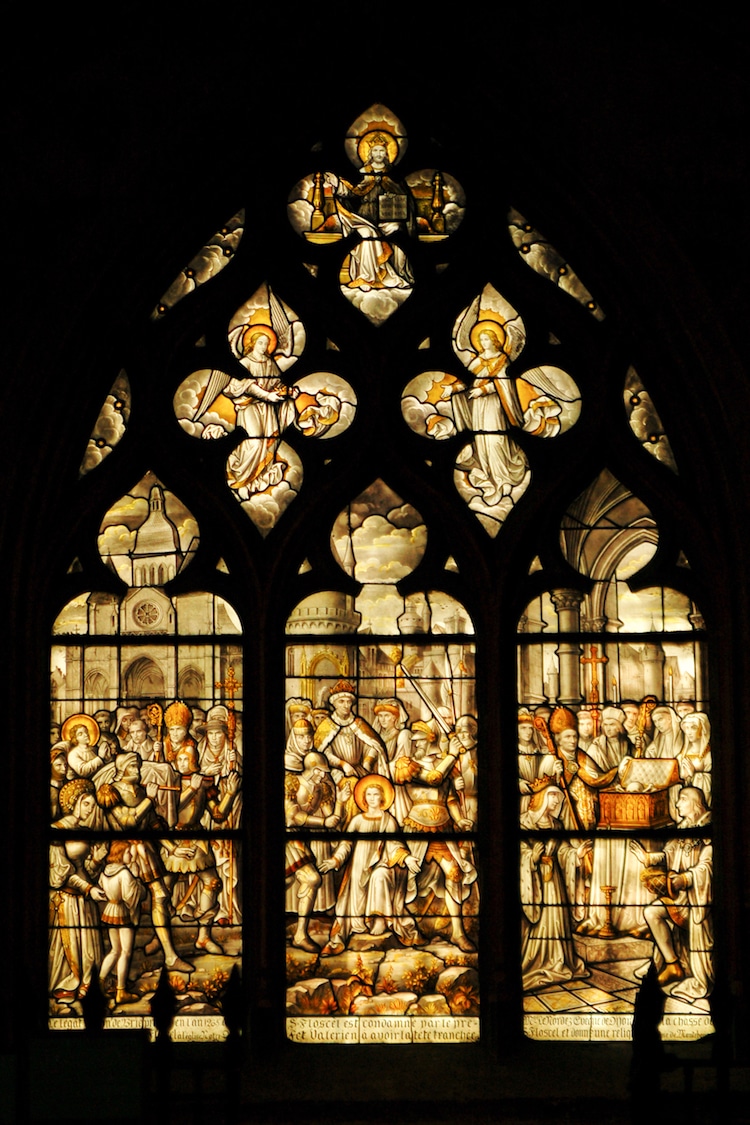

By the Middle Ages, stained glass windows could be found in countless Catholic churches across Europe. Until the 12th century, however, these windows were relatively simple, small in scale, and outlined by thick iron frames. This is because Romanesque architecture—a style characterized by thick walls and rounded forms—dominated architectural tastes.

Beaune Notre-dame, France (Photo: Stock Photos from lynnlin/Shutterstock)

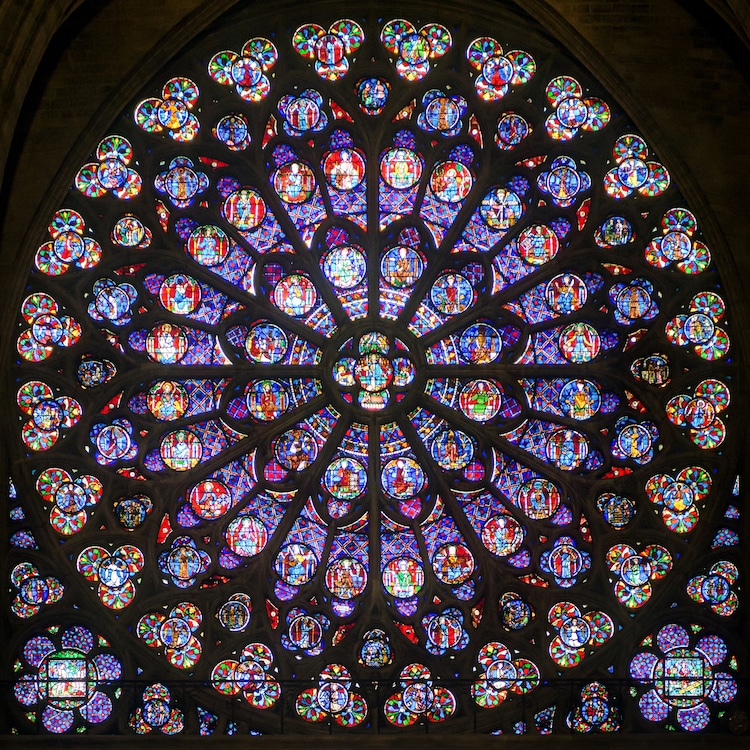

In the 12th century, however, the Romanesque style was replaced by Gothic architecture. Unlike Romanesque buildings, churches and cathedrals built in this style illustrate an interest in height and light. This focus is evident in all aspects of Gothic design, including sky-high spires, delicate, thin walls, and, of course, large stained glass windows.

Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris (Photo: Stock Photos from Viacheslav Lopatin/Shutterstock)

Gothic windows typically come in two forms: tall and arched lancet windows or round rose windows. In both cases, they’re often monumental in scale and rendered in meticulous detail—an achievement made possible through the use of tracery, a decorative yet durable form of stone support. Because of both their size and intricacy, Gothic stained glass windows were able to let in more dazzling light than ever before.

ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE

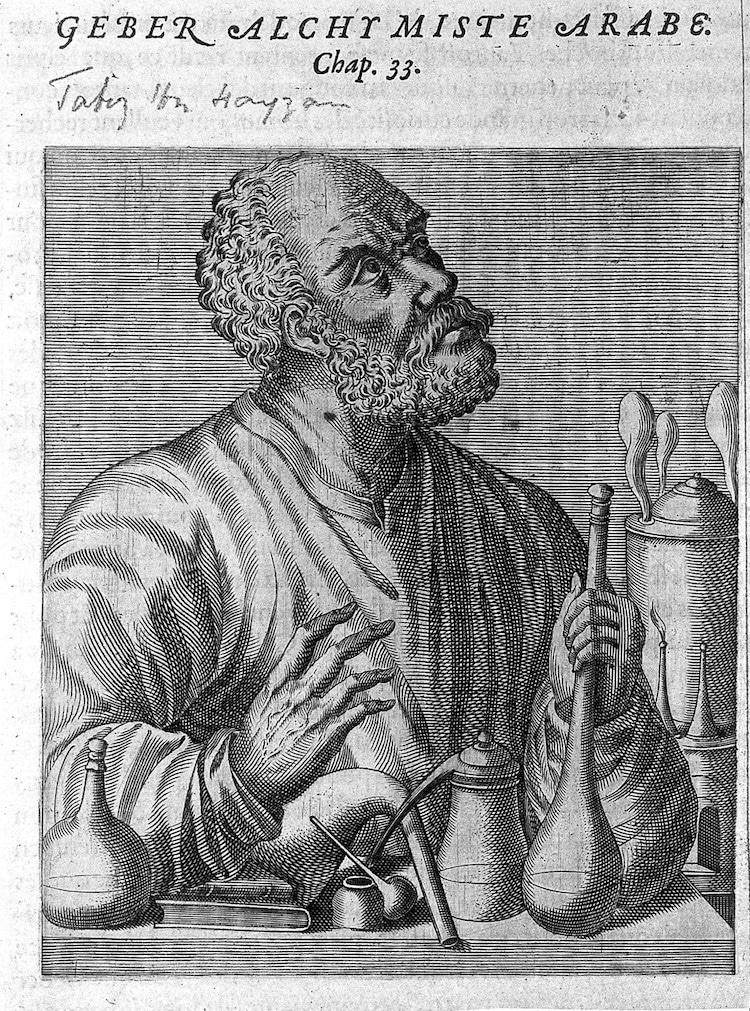

By the 8th century, stained glass had made its way to the Middle East. The magic behind the medium is discussed at length in Kitab al-Durra al-Maknuna (“The Book of the Hidden Pearl”), a colored glass cookbook written by Persian chemist Jābir ibn Ḥayyān.

Jabir ibn Hayyan Geber, Arabian alchemist (Photo: Wellcome Collection CC BY 4.0)

In this manuscript, Jābir ibn Ḥayyān offers dozens of “recipes” for colored glass and artificial gemstones. To the author, experimentation was key to creating high-quality glass. “The first essential in chemistry is that you should perform practical work and conduct experiments, for he who performs not practical work nor makes experiments will never attain to the least degree of mastery,” he wrote. “Scientists delight not in abundance of material; they rejoice only in the excellence of their experimental methods.”

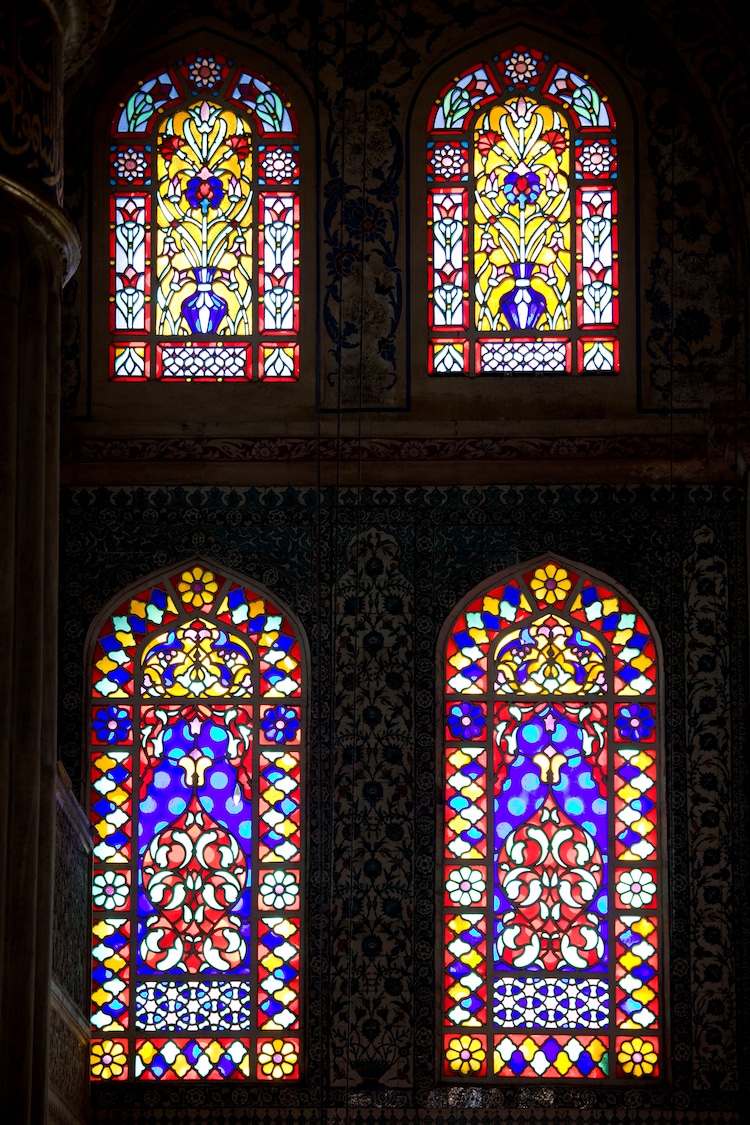

At this time, glass industries were thriving in Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and Iran. Here, artisans adopted and adapted the ancient Roman medium, using it to adorn mosques, palaces, and other staples of Islamic architecture with windows rich in color and complex in pattern. These pieces became increasingly ornate over time.

The Blue Mosque (Photo: Stock Photos from Artur Bogacki/Shutterstock)

Historians believe that Jābir ibn Ḥayyān’s creative approach illustrates the Islamic approach to the stained glass practice. “Muslim and non-Muslim glassmakers working in the Islamic areas . . . were extraordinarily creative,” historian Josef W. Meri writes in Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, “and in tune with the general evolution of Islamic art, brought this craft to a new technical, technological, and artistic heights.”

AMERICAN ARTS AND CRAFTS

In the 19th century, American artisans transformed the ancient art of stained glass into a modern art form. This approach is particularly evident in the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, the pioneer of the Prairie School movement, a style of architecture and interior design that emphasizes craftsmanship and a connection to nature.

Clear windows with pops of stained glass became an intrinsic part of Wright’s Prairie School interiors. These accents materialized as “ribbons of uninterrupted glass” featuring “geometric abstractions unique to each building for which they were created,” making each window a one-of-a-kind work of art.

At the same time that Wright was producing his windows, another American glassmaker successfully reinterpreted the ancient art form. In 1885, Louis Comfort Tiffany established the Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, a New York City-based studio that produced spectacular stained glass lamps.

While these once-popular lamps fell out of fashion in the middle of the 20th century, they recently saw a revival and, today, remain coveted collector’s items.

STAINED GLASS TODAY

Today, contemporary stained glass artists keep the age-old art form alive. Like their 20th-century predecessors, these artists continue to come up with creative new ways to reinterpret the ancient craft.

Tom Fruin, ‘Kolonihavehus’ (Photo: Stock Photos from Edi Chen Lopatin/Shutterstock)

Whether they’re using sparkling glass to spruce up the New York City skyline, enhance an enchanting cabin, or make a botanical garden bloom in new ways, these artists prove that stained glass is anything but outdated.

mymodernmet.com

kcontents